Kei Nishikori: On Retirement

“Ending a career due to injury is the worst scenario for an athlete.”

When Kei Nishikori calmly uttered this sentence in an interview, the former world No. 4 and a leading figure in Asian men’s tennis was facing the most sensitive turning point in his career. The idea of retirement, which emerged last year, became tangible and real after the Cincinnati event this year. Over the past three years, he has pushed the boulder of injury recovery uphill like Sisyphus, only to watch it roll back down repeatedly—wrist injuries, back pain, surgeries, rehabilitation, an endless cycle.

Yet he decided to carry on.“Part of it is because of my pride and determination. Also, I always feel my talent is too great to just stop now.”Behind this statement lies the full weight of a 36-year-old athlete.

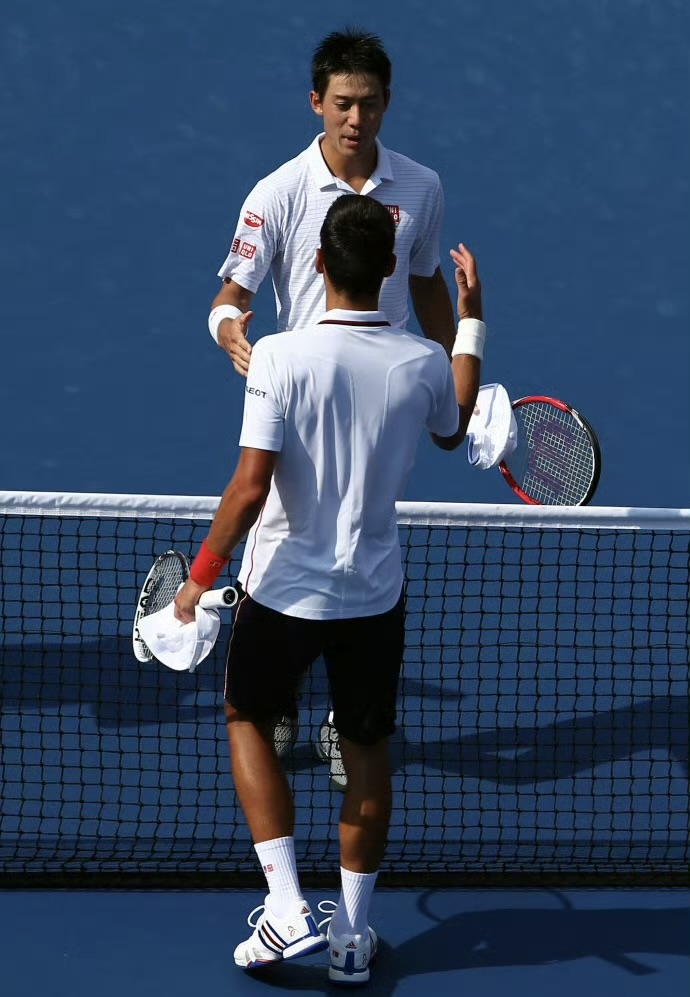

Kei Nishikori’s career is an epic of pioneering Asian tennis. In the 2014 US Open final, he became the first Asian male player to reach a Grand Slam singles final. His agile baseline movement, sharp backhand down the line, and incredible retrievals formed his unique tennis artistry. He wasn’t a power hitter, but used precision and intelligence to carve out his own territory in a field dominated by giants.

But talent is both a gift and a burden. It gives you wings to reach the peak but also makes it harder to accept the reality of no longer being able to fly. For Nishikori, this immense talent became a moral responsibility—to himself, to his fans, and to Asian tennis—to keep moving forward.

Injuries are the cruelest opponent for athletes because they never offer a fair fight. You can study Federer’s backhand or figure out Djokovic’s defense, but how do you negotiate with your own body? When muscle memory is clouded by pain, when the kinetic chain breaks, when recovery speed can’t keep up with aging, every athlete faces the ultimate question: when to let go?

Nishikori’s choice reveals the complex psychological landscape of a professional athlete. It’s not just about calculating competitive form but struggling with identity. When the identity of being a tennis player that has defined you for twenty years is at risk of being stripped away, how much courage does it take to redefine yourself?

“I still need to fight for a year to regain my tennis level,” the word “regain” carries particular weight here. It doesn’t point to new heights but to a desire to return to the former self. This nostalgic struggle is often the most heartbreaking and admirable aspect of professional sports.

Such stories are not uncommon in tennis history. Nadal’s prolonged battle with foot injuries, Del Potro’s recurring wrist problems, even Federer’s final dances—all have been graceful or grueling negotiations with a betraying body. The difference lies in when they sign the final agreement at the negotiation table.

Nishikori’s persistence perhaps reflects the paradox of modern athletes’ extended careers: medical and training science allow us to stay longer on the court but also prolong the painful farewell process. In the past, 30 might have been a natural endpoint; now it has become a moment requiring an active choice.

For spectators, we often want heroes to fight forever but seldom consider the cost of the battle. Nishikori’s struggle reminds us that every decision to continue or quit is backed by countless mornings spent enduring pain, technical frustrations, ranking declines, and ruthless overtaking by younger opponents.

Yet he remains on the training court. Still adjusting his serve to accommodate his post-surgery wrist, still enduring tedious rehab exercises, still dreaming of returning to the center court—even if just for a fleeting moment.

This may be the most moving part of sportsmanship: not a myth of invincibility, but the dignity of choosing to fight despite knowing failure is possible. Nishikori’s pride and willpower are not empty slogans but daily concrete choices—choosing injections, choosing ice therapy, choosing to board yet another tour flight.

Tennis is ruthless because it never waits. The post-2000 generation has already risen, the pace of matches keeps evolving, and an injury-plagued veteran must battle both time and trends simultaneously.

But the beauty of tennis is that it always offers possibilities. As long as you can stand on the court, there is room to create miracles—perhaps not the miracle of a US Open final, but a clean, decisive winner after a long absence, a match that makes the crowd rise and applaud, a lesson in tennis wisdom for the younger generation.

Nishikori’s final chapter is yet to be written. Whether next year, the year after, or someday when he truly hangs up his racket, his legacy has already surpassed wins and losses. He proved that Asian male players can compete on tennis’s highest stage, demonstrated how skill and will can compensate for physical limits, and now shows how an athlete faces the twilight of his career with dignity.

His talent is indeed too great to stop now—not because the world needs more victories, but because the boy once chosen by talent still needs time to say a proper farewell to his tennis life. And in that farewell, every swing may be the deepest tribute to the sport.

Perhaps this is the real reason Nishikori refuses to leave due to injury: not to deny the end, but to choose to end on his own terms. Before the final whistle blows, he still wants to play a few more rounds—for himself, for his talent, and for all who refuse to let injury steal their story.(Source: Tennis Home Author: Mei)

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App